Robinson’s Enduring History and Humanity

Cornel West’s 1995 introduction to Jackie Robinson’s autobiography describes Robinson as “a great American who refuses to be a mythical hero.” Myth, in this context, refers to the process of simplification that occurs when the infinite depths of a person’s experience, character, and significance are reduced to a few images or anecdotes. What are we to make of the reality that every American 8th grader knows a thing or two about Jackie Robinson, but few take the time to gain a fuller picture of his remarkable life?

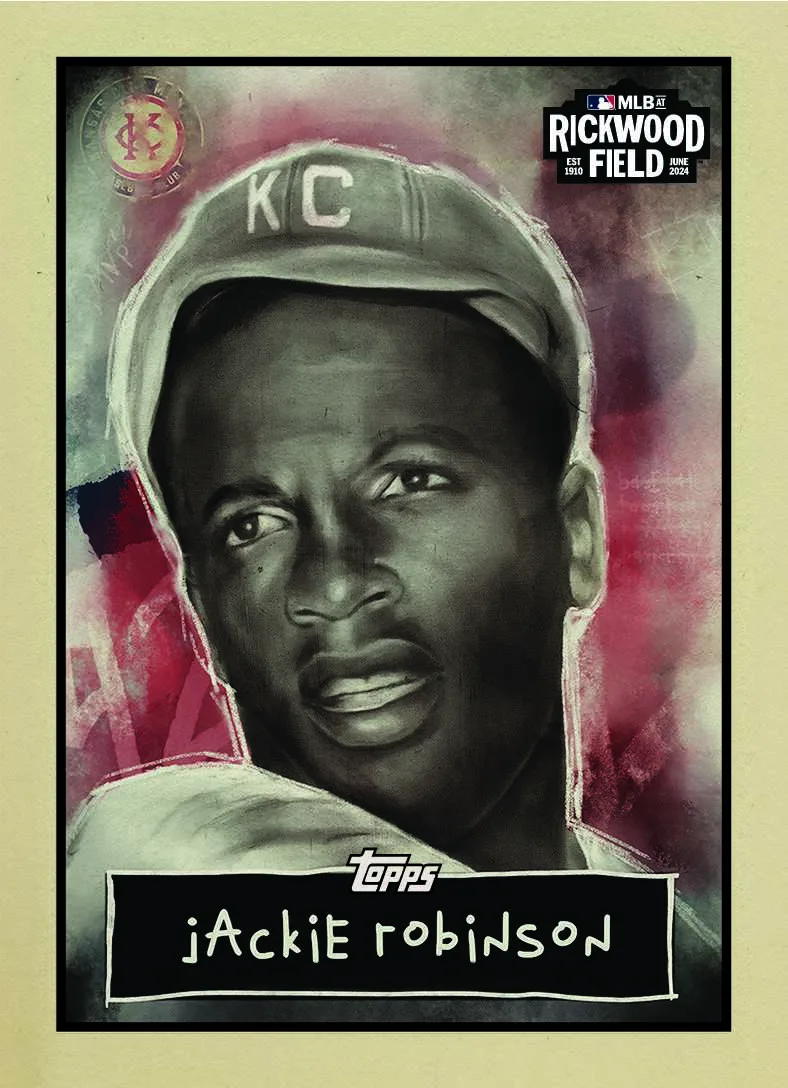

And as the MLB prepares to honor the Negro Leagues and Negro Leaguers with a nationally televised regular season game on FOX between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants at Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Alabama, on 6/20, it’s important to go beyond the myth and discover the great and steadfast strength of character that formed the core of Jackie Robinson’s life on and off the field.

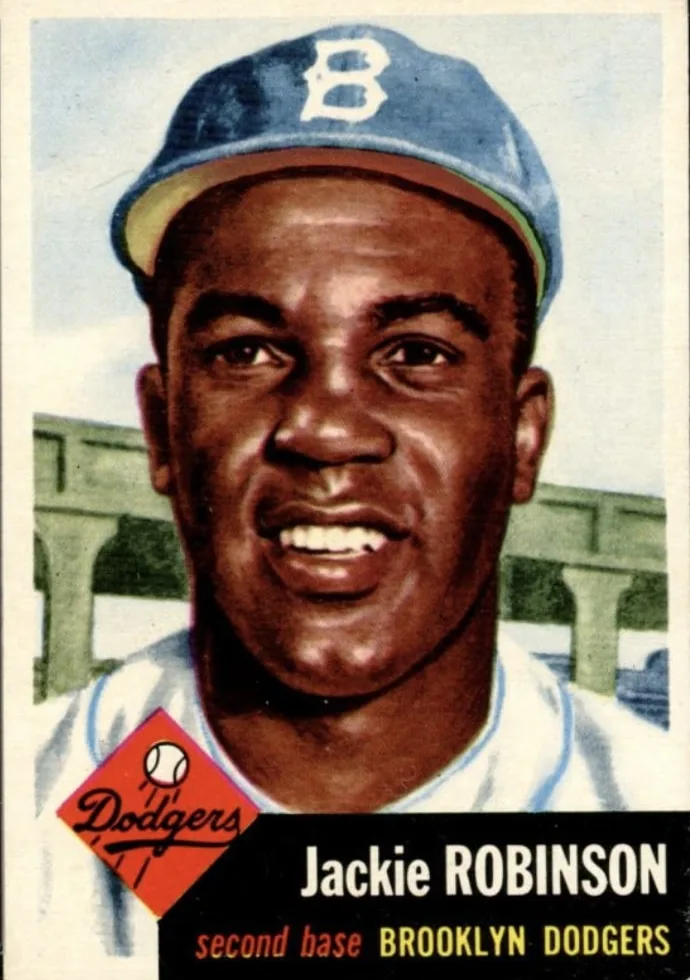

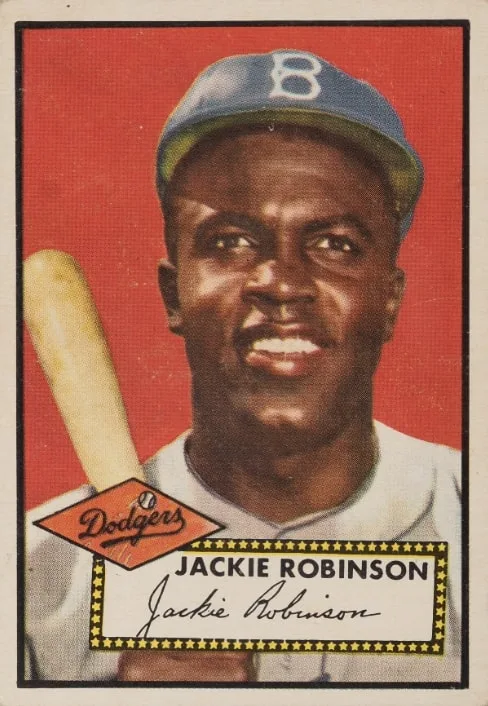

1952 Topps Baseball #312 Jackie Robison

Robinson’s athletic prowess was evident by the time he finished high school in 1937, but after lettering in baseball, football, track, and basketball, a brief stint at Pasadena Junior College, and lettering in the same four sports at UCLA, Robinson quit college, just a few credits shy of graduation, convinced that “no amount of education would help a Black man get a job.” Hoping to help relieve some of his mother’s financial stress, Robinson took a job as an athletic director with the National Youth Administration.

It was at UCLA that Robinson met his future wife, Rachel, but they would not marry until 1946. In the Fall of 1941, Robinson played a season of football with the racially integrated Honolulu Bears, but after Pearl Harbor was attacked in December of that year, Robinson – in the prime of his athletic years – put his sports career on hold to serve in the military. Incredibly, Robinson did not play organized ball again until 1945, when he played 47 games with the Kansas City Monarchs.

Baseball and the Democratic Ideal

Surprisingly, Major League Baseball never explicitly prohibited Black players; it was an unspoken agreement reflecting a cultural consensus—and Brooklyn Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey believed the culture was changing. To be sure, Jim Crow laws were still prevalent in the 1940s, but for the first time since Reconstruction, desegregation and civil rights were becoming a national discussion.

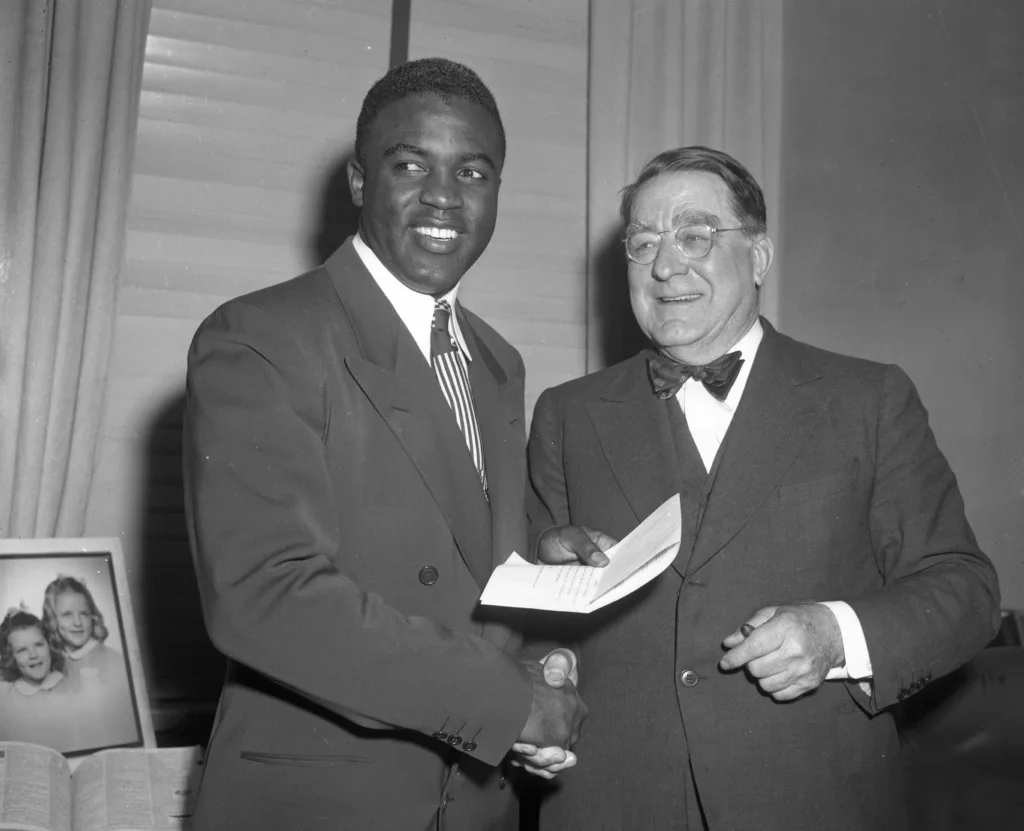

Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey (Photo Reproduction by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images)

Remarkably, this difficult and sometimes bitter revolution in American culture arrived at its first full expression on a baseball field. Before Brown v. Board of Education, and almost a full generation before civil rights legislation formalized and institutionalized the cultural shift, Rickey and Robinson agreed to a very strategic plan. They believed that if integration worked on the ball field, other institutions would follow suit.

The riveting description in Robinson’s autobiography of his first long conversation with Branch Rickey includes Rickey’s solemn summation: “A baseball box score is a democratic thing. It doesn’t tell how big you are, what church you attend, what color you are, or how your father voted in the last election.” Maybe it’s unavoidable that when a particular individual’s life intersects so sharply with a social myth, the life itself takes on mythic proportions.

Hardship and Achievement

Rickey had warned Robinson of the abuse he would have to endure: beanballs, infuriating racial epithets, even physical attacks. Robinson considered it all carefully, hesitating when, for a moment, he suspected Rickey was “looking for a Negro who [was] afraid to fight back,” but finally accepted his part in the “noble experiment.” Parallel to these intense emotional and psychological negotiations, on the other side of the prejudice and abuse, there was the baseball.

Jackie Robinson attempting to steal home (Photo by Bruce Bennett Studios via Getty Images Studios/Getty Images)

After one season with the minor league club in Montreal, at the age of 28, Robinson made his Major League debut at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947. Under unimaginable pressure, Robinson racked up 175 hits and 29 stolen bases in his first season. His .297 average earned him baseball’s inaugural Rookie of the Year award, and the Dodgers made it to the World Series that year.

Robinson’s cumulative .313 average and 200 career stolen bases during his ten-year career were accompanied by one MVP award (1949), a World Series victory (1955), and six All-Star appearances. But even when he retired in 1956, everyone understood that his singular career and life meant so much more than his Hall-of-Fame-worthy statistics could reveal.

A Continuing Struggle

In the epilogue of his autobiography, Robinson wrote, “I had to fight hard against loneliness, abuse, and the knowledge that any mistake I made would be magnified because I was the only Black man out there.” Robinson had successfully shouldered a burden far beyond his pay grade. By 1959, just three years after his retirement, every team in baseball included Black players on their rosters. In 1997, with recognition of what Robinson had accomplished on and off the baseball field still deepening, MLB retired #42 from the game.

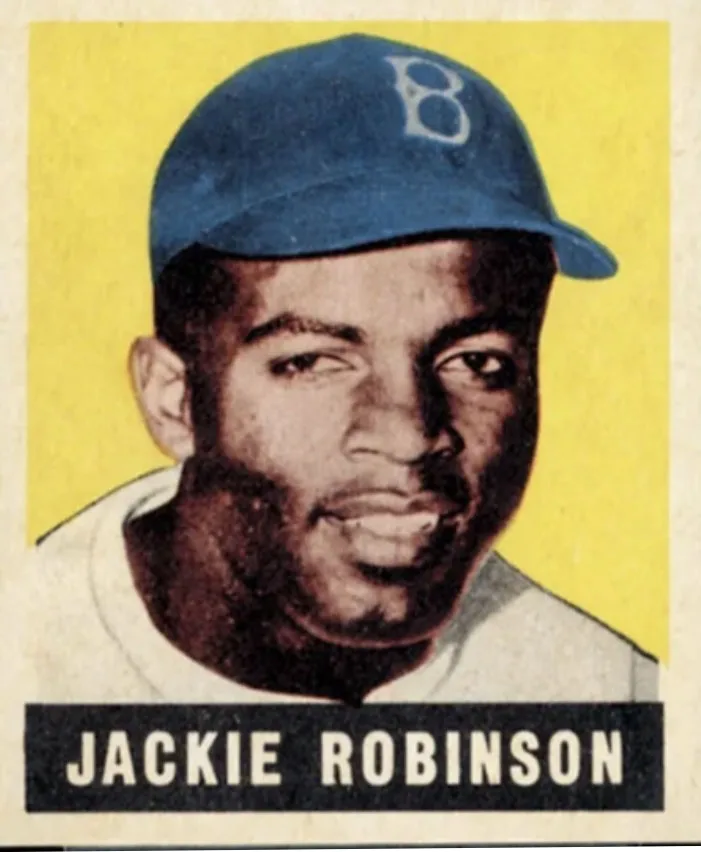

1948 Leaf Baseball #79 Jackie Robinson

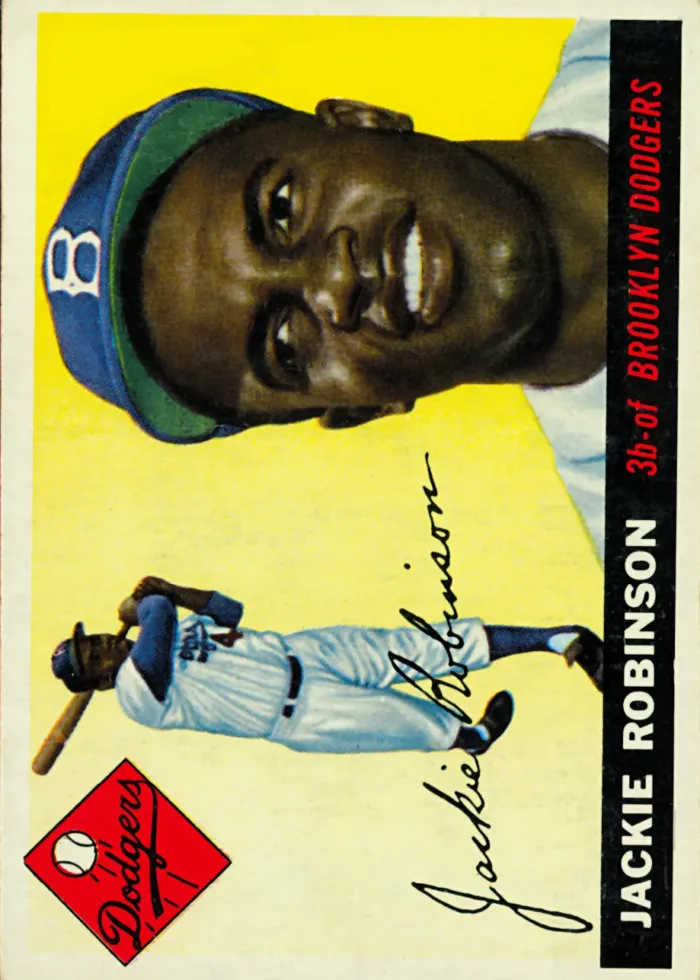

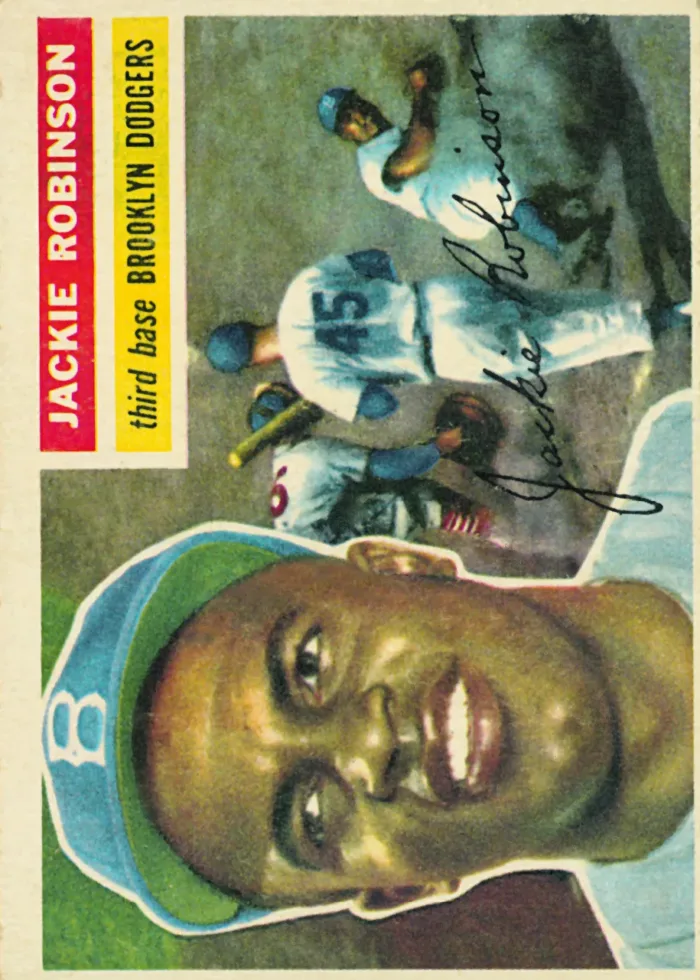

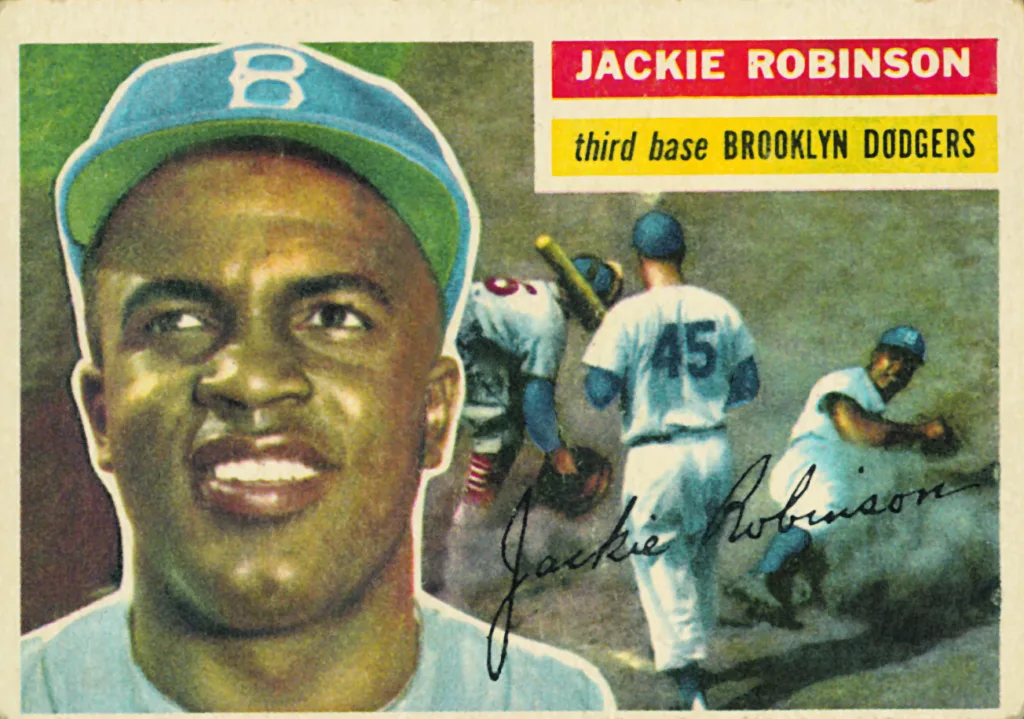

1956 Topps Baseball #30 Jackie Robinson

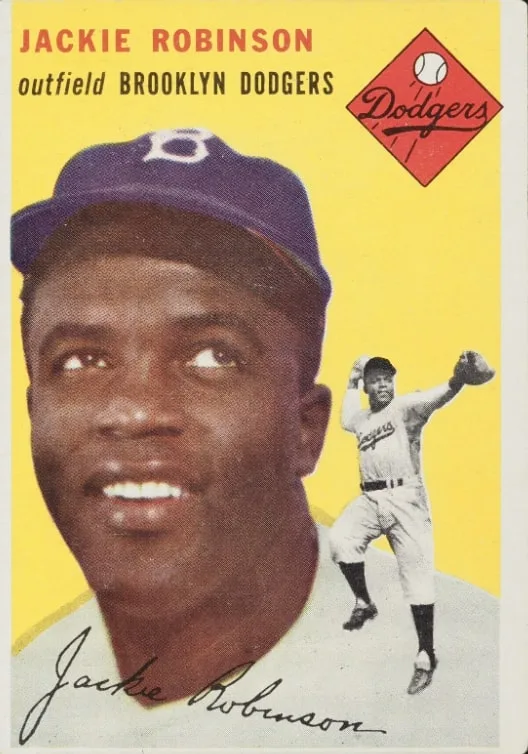

In order to meet demand and to honor his remarkable life, Jackie Robinson cards continue to be printed almost every year, but the cards printed during his playing career remain the most highly prized. Robinson’s rookie card is the 1948 Leaf card (#79), but his 1950 Bowman and 1952 Berk Ross cards are also widely considered to be treasures. The sequence of Topps cards printed in his name between 1952 and 1956 are some of the most iconic cards in the history of The Hobby.

Jackie Robinson Topps Baseball cards, 1952 – 1956

The civil rights legislation of the 1960s was certainly a milestone in American history, and Robinson worked closely with the NAACP throughout those pivotal years. If Branch Rickey was justified in calling Robinson’s inclusion in the MLB a “noble experiment,” America itself might (someday) be understood by the same phrase.

Jackie Robinson and more than 200,000 others marched in the 1963 March on Washington. (Photo by Steve Schapiro/Corbis via Getty Images)

In 1970, Robinson exchanged a series of mutually standoffish letters with President Richard Nixon, whom Robinson had supported for President in 1960. In commentary on these letters in his autobiography, Robinson remarked, “It is not enough for one man to admire another because of his past accomplishments.” Robinson suspected Nixon’s placating language was “double-talk,” and concluded, “In the face of being written off by Mr. Nixon’s party and being taken for granted by Democrats, we must develop an effective strategy and learn how to become enlightenedly selfish to protect Black people when white people seem consolidated to destroy us.”

Strikingly, it is in this direct and confrontational voice that Robinson (still) speaks to us from beyond his mythology. He indeed broke an important barrier on the playing field, but he was also aware that it would be too easy to imagine all the crucial progress as being behind us. Hank Aaron said, “Jackie’s character was much more important than his batting average.” It is tempting to add: to the extent that America understands and emulates that character, America is bound to succeed in the long run.