The Greatest Pitcher Ever

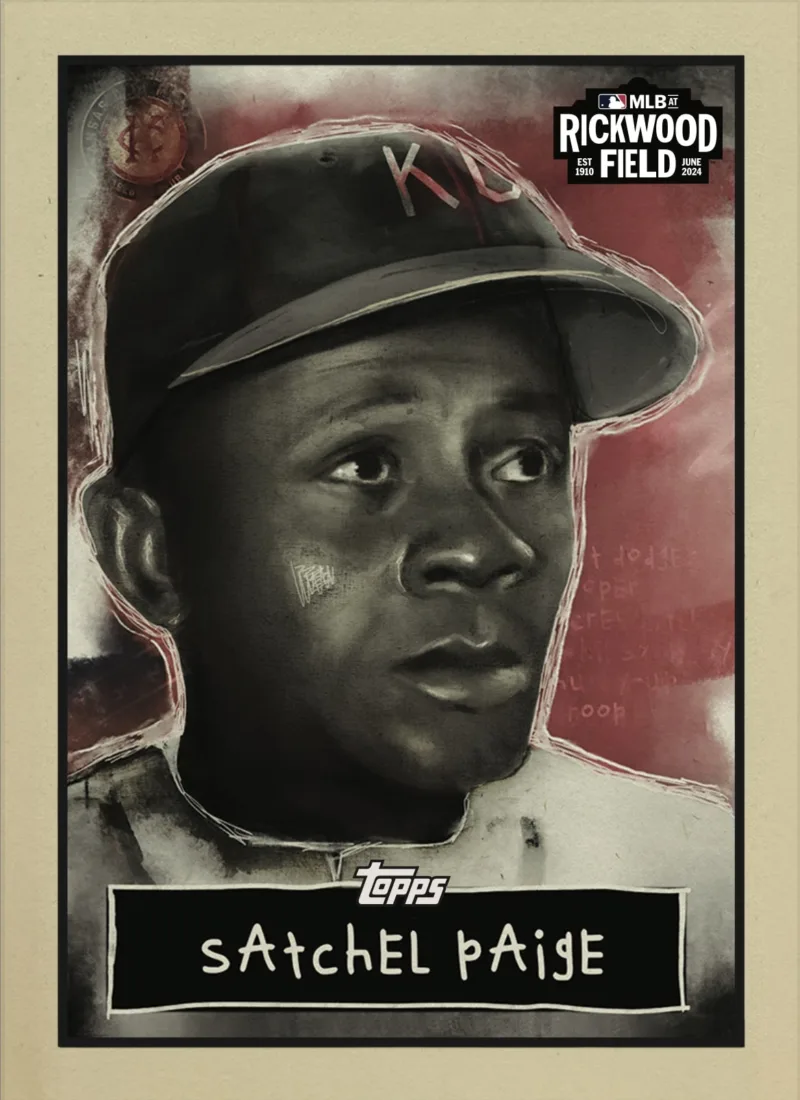

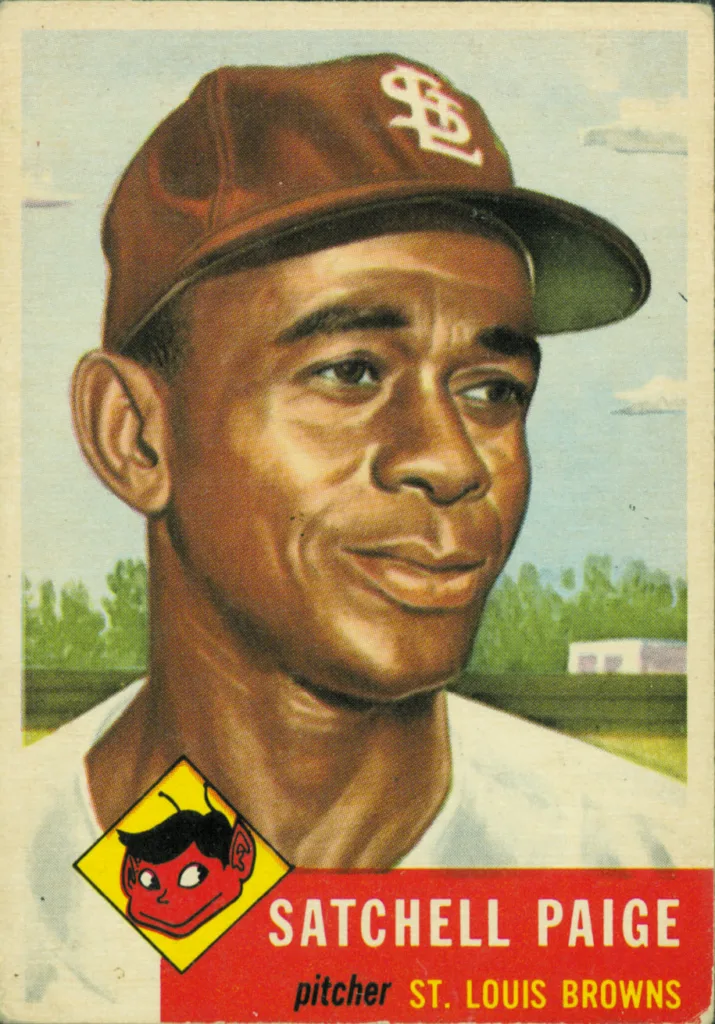

In 1953, Topps’ sophomore set featured prints of beautiful opaque watercolor paintings modeled on photographs of the players. Each is remarkable in its way for the artistry, but one card stands apart, inviting fans and collectors to examine more closely the life and times of the man who really might have been the best pitcher ever to live.

1953 Topps Baseball #220 “Satchell” Paige

“Satchell,” as his name appears on both the front and back of the card, was in his mid-to-late-40s when the painting was commissioned, and the placid features on his distinguished face invite the viewer to think not only about the pitcher, but also about the man.

However, a combination of factors makes it difficult (and perhaps ultimately undesirable) to disentangle the man from the mythology entirely. The misspelling of his name contributes to this air of mystery, as does the fact that no photograph of Paige ever appeared on a Topps card. In the liminal space created by American segregation, men and women were ignored, humiliated, and overlooked, but consequently, myth flourished.

Satchel Paige: Man and Myth

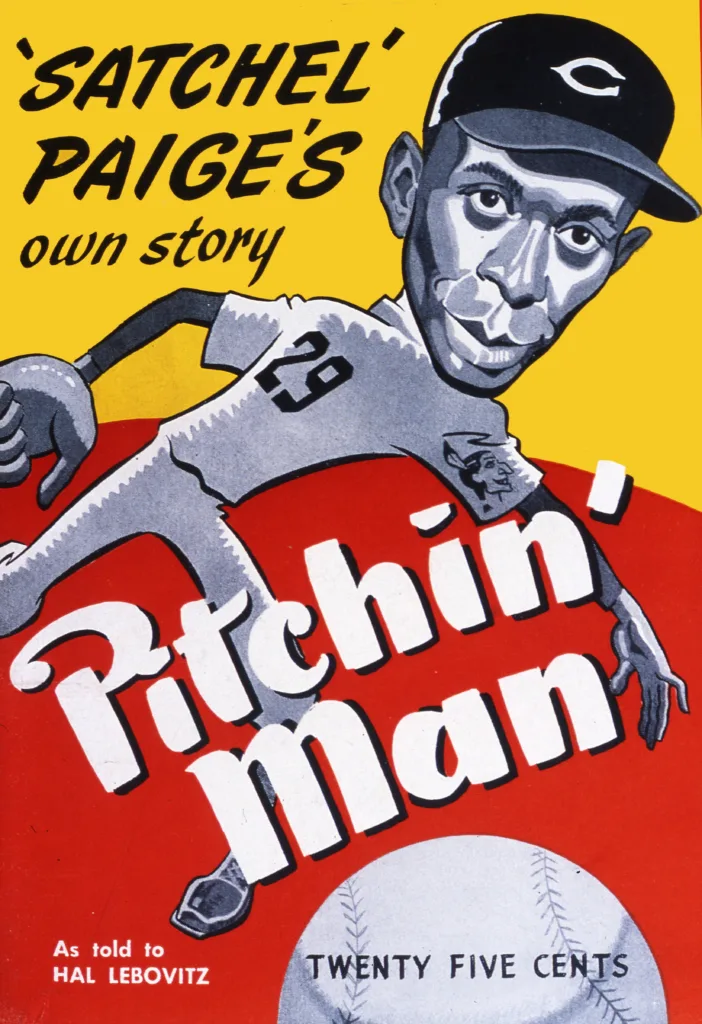

In the 21st century, some readers of Paige’s two autobiographies are perplexed and unsatisfied by the writings, detecting what they believe to be a note of minstrelsy in Paige’s voice, a hokey “aw shucks” posture meant to appease white American readers. The mythology embarrasses readers who see something clownish in Paige’s showboating and his fondness for jocular storytelling. However, interpreted differently, it may be that Paige found a way to retain a sense of dignity by preserving an element of mystery even as he told his own story.

CLEVELAND – 1949. Satchel Paige’s book Pitchin’ Man featured an artist’s rendering of the mound ace. (Photo by Mark Rucker/Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images)

Born in Mobile, Alabama, the birth certificate of one LeRoy Page, spelled without the “i,” puts his birth date as July 7, 1906. But his mother’s Bible said 1904, and the 1953 Topps card says he was born September 11, 1908. In any case, the landmark Plessy v. Ferguson decision had recently established the “separate but equal” doctrine as the dubious legal principle that would define the Jim Crow era. As W.E.B. DuBois had famously predicted, racial segregation would be the problem of the 20th century, and Paige’s pitching career was destined to traverse that line.

Given the unmistakable injustices of the period, it may seem frivolous to talk about the segregation of sports. But as Black Americans were barred access from so many avenues and institutions in public life, the pitching adventures of Satchel Paige became the stuff of legend, and Paige attained folk hero status.

Undoubtedly, many black Americans felt pride seeing players like Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, and Roy Campanella break the color barrier in baseball. However, Paige seemed to come from another pantheon, where his peers were the mythic John Henry and John the Conqueror. In his second autobiography, Paige happily cited one sportswriter who described him as a “technicolor Paul Bunyan.”

There’s Only one Satchel Paige

Many fans enjoy the tall tales and incredible anecdotes concerning Paige – how he could throw a fastball that would put a man’s cigarette out without knocking it from his mouth, or how he was clocked at 103 mph – but as soon as we are convinced that it must all be exaggeration, the myth steps out of the shadows as a man offering plain proof. In 1966, for instance, Kansas City signed Paige as a kind of publicity stunt, inviting the sixty-year-old retiree to throw a few innings. Paige accepted the offer; the result: three scoreless innings.

In his second autobiography, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever, Paige recalls that by 1926, people were taking notice. He admits that it angered him whenever anyone told him it was “too bad” that he couldn’t play in the majors because of his color. In one bizarre incident, the head of the minor league Chattanooga Lookouts, Stran Niglin, offered Paige $500 to pitch against the Atlanta Crackers, with one caveat: Niglin had to paint Paige white. Talked out of it at the last minute, Paige’s analysis is remarkable: “I think I’d have looked good in white-face. But nobody would have been fooled. White, black, green, yellow, orange—it don’t make any difference. Only one person can pitch like me.”

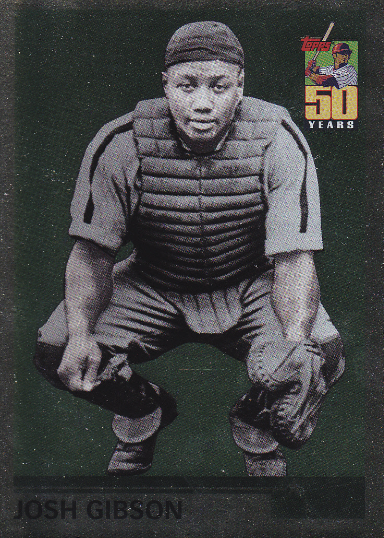

2001 Topps Series 2 What Could Have Been #WCB-1 Josh Gibson

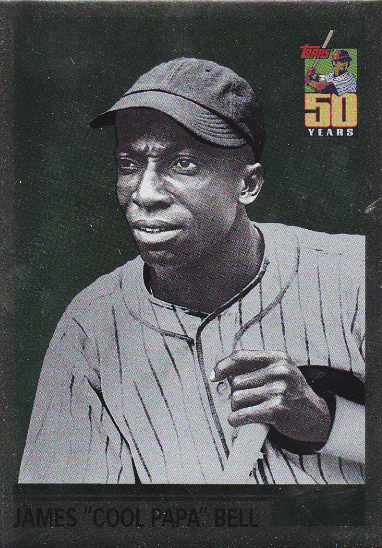

2001 Topps Series 2 What Could Have Been #WCB-4 James “Cool Papa” Bell

By 1951, as the MLB accepted integration as the norm, attendance at Negro League games dwindled, and the public gradually shifted its attention. Topps started making cards the following year, and as a result, most of the best players to ever play in the Negro Leagues—including Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, and Oscar Charleston— were never issued cards. Their absence deepens the mystique of the 1953 Satchel Paige card, which stands as a bridge to that era.

Paige’s Deeply Human Legacy

According to some reports, the younger generation of athletes who had moved from the Negro Leagues into the MLB in the late 40s, including teammate Larry Doby, believed that Satchel’s jovial humor was an embarrassment, and feared that he was setting back the cause of integration. It was a generational divide, and the realism and seriousness that characterized the Civil Rights movement made it difficult to see Paige’s humor clearly.

If our preference for the cerebral has made Satchel’s exaggerated movements, his famous hesitation pitch, and his rambling anecdotes seem like a minstrel act, perhaps our preference reveals more about us than it does about him. There are layers in his personality, and the mythic stories told by him—and about him—invite us to study his career more closely. Zora Neale Hurston, just a bit older than Paige, wrote in 1934, “I love myself when I am laughing. And then again when I am looking mean and impressive.”

Satchel Paige showed the crowd his laughter and was famous for jesting with teammates and opponents. But he never backed down from a challenge, and he outlasted all of his contemporaries. Bob Feller said Paige was the best pitcher he ever saw. Joe DiMaggio called him “the best I’ve ever faced and the fastest.” The world may have known Paige by his sense of humor, but no matter how goofy that windup looked, it’s safe to say that, to the few men who saw him from inside a batter’s box, no one looked meaner or more