Experience the Dreams of Rickwood Field

When the St. Louis Cardinals face off against the San Francisco Giants at Rickwood Field on June 20, 2024, the game will be the centerpiece in an extended tribute to the Negro Leagues. The stadium, which was home to the Birmingham Black Barons, has become a living time capsule.

(Photo by Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

It will be a moment made possible by the memories and shared vision of a few sentimental preservationists. Like so many of the early baseball stadiums, Rickwood Field had fallen into disrepair by the late 1980s and was no longer used by any pro teams. At its lowest moment, the stadium was abandoned, and talk of tearing it down was not uncommon. That’s when a group of locals got together, calling themselves the Friends of Rickwood, and decided to save the ballpark.

Then, in the early 1990s, film director Ron Shelton and lead actor Tommy Lee Jones teamed up to make the movie Cobb. They needed a stadium that felt like it was from the early 20th century, and Rickwood Field was perfect. That’s when the renovations began, and by 2005, the Friends of Rickwood had spent more than two million dollars restoring the park. Now, with restored seating, a renewed main entrance, a new roof, and other touch-ups, a visit to the stadium is essentially a time travel experience.

An Evolving Architectural Masterpiece

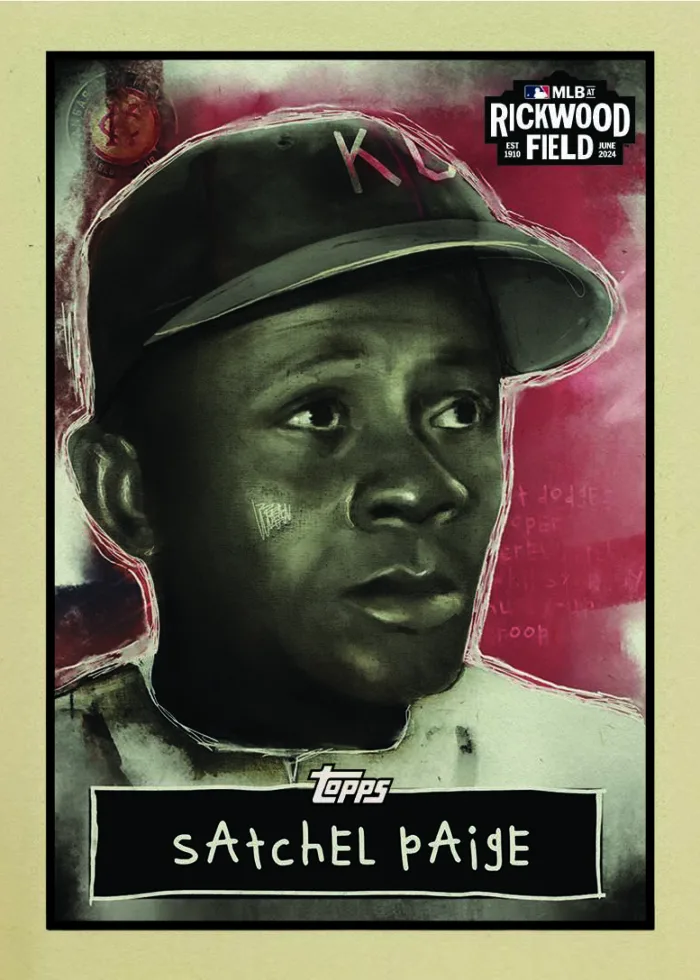

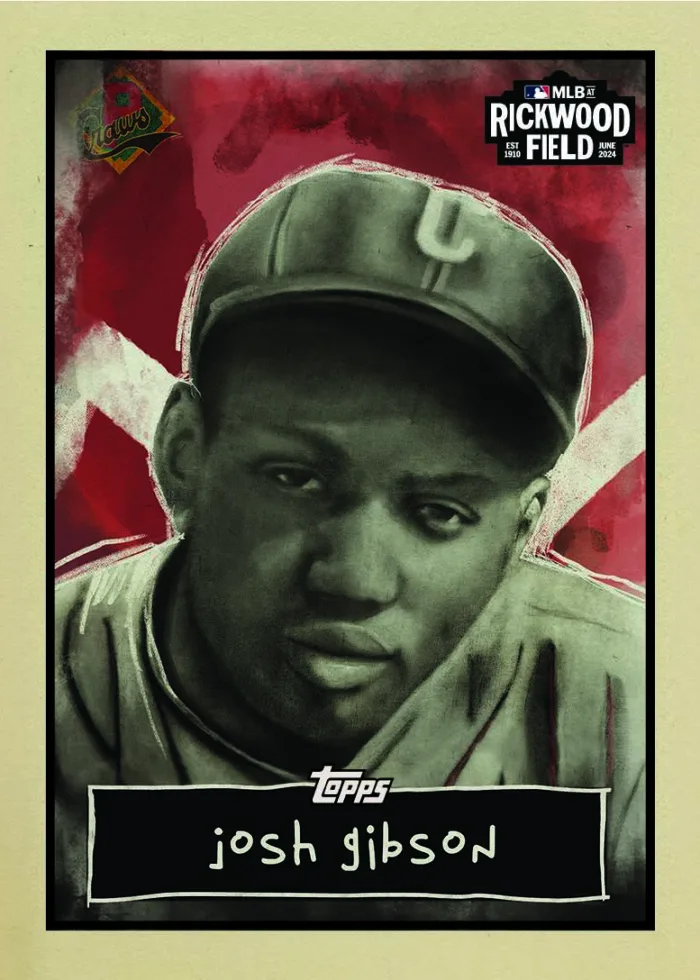

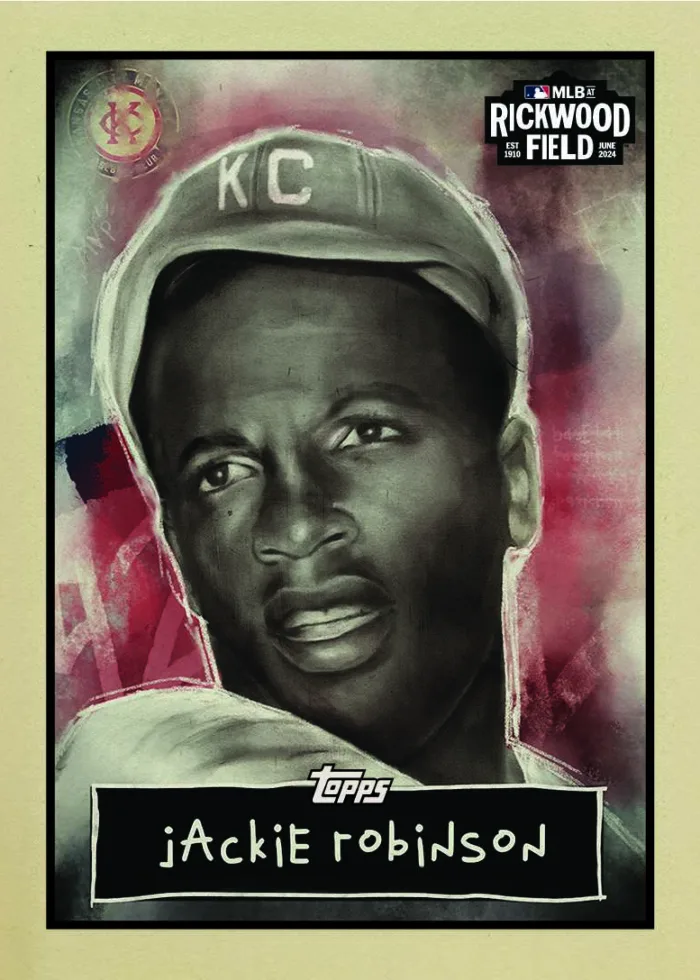

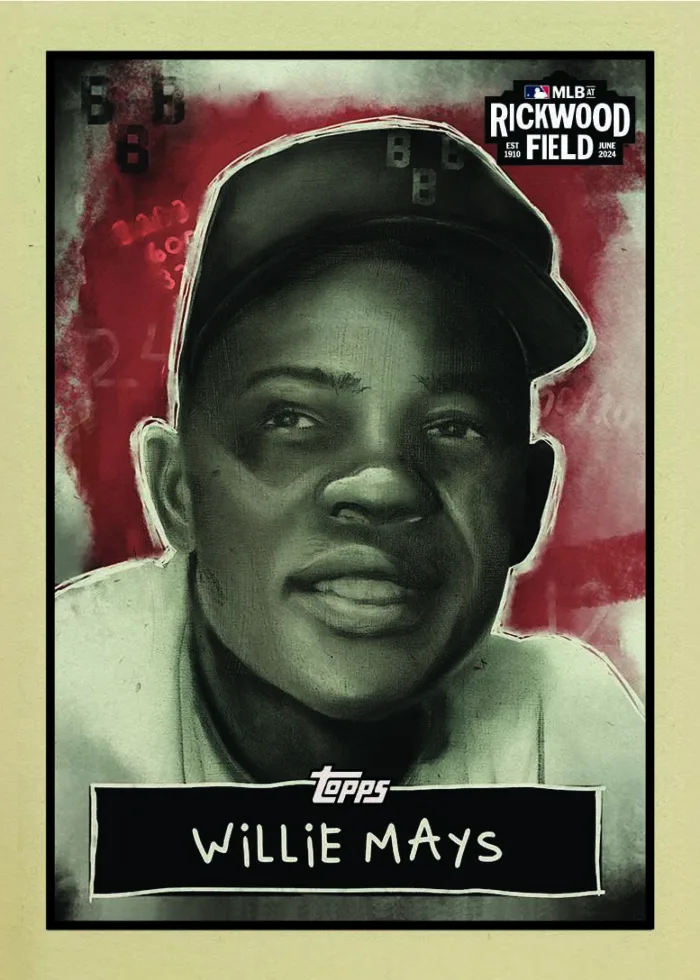

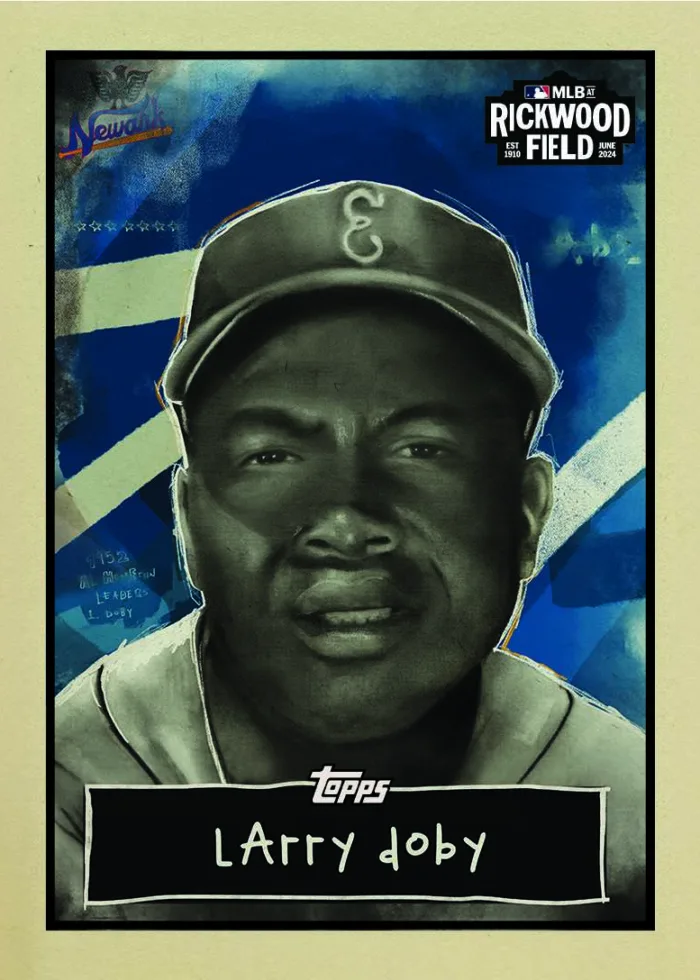

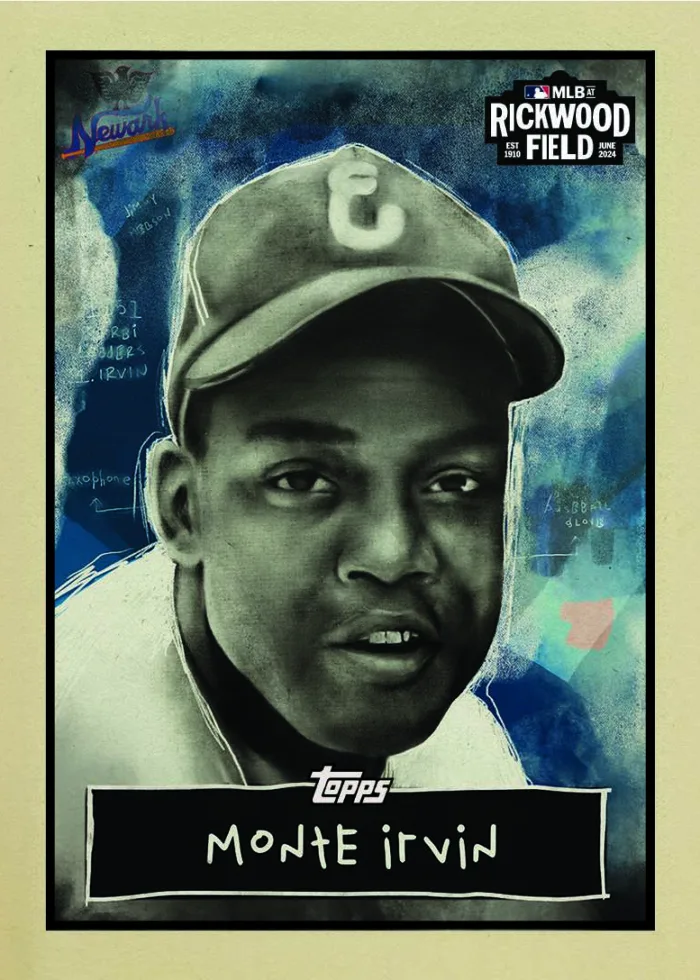

As part of this summer’s celebration, Topps is offering a six-card set – the MLB at Rickwood Negro League collection – which features six of the greatest athletes to have played in the stadium. The set features art by Micah Johnson and includes cards for Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Monte Irvin, and Larry Doby.

But as the Negro League stars and other Hall-of-Famers are honored, and even as the Cardinals and Giants bring MLB action to Birmingham, Rickwood Field itself is the main character in the drama. It is now the oldest professional ball field in America and has been an evolving architectural masterpiece since its opening day, August 18, 1910.

As a rule, preservation has not been America’s strong suit. As the famous line from Field of Dreams put it, “America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again.” Rarely, as in the case of the Old State House in Boston or the Flatiron Building in New York City, an American structure seems too important to tear down. Rickwood Field is now that kind of place.

From the first upgrade (electric fans in 1912 to cool the crowd) through lights for night games (1936), the addition of a ladies’ restroom (1948), various coats of paint, and a new scoreboard or two, Rickwood Field has accumulated memories and character. If certain places can become “wise,” or hallowed, offering self-awareness and insight to those visiting, Rickwood Field has gradually become that place.

Birmingham and Baseball

The city of Birmingham, Alabama, was born late, in 1871, during Reconstruction. It is not, as Paul Hemphill has argued, an old Southern city. Instead, Birmingham was among the first “New South” cities, a product of the optimism and new energy emerging in the wake of the devastating Civil War. Birmingham was almost a “Wild West” town in the late 1800s, and two things gave the city a sense of identity and direction.

The first was the iron industry, and the Woodward Iron Company was undoubtedly Birmingham’s financial engine. The mines and mills gave stable employment to so many of the city’s men. The other pillar of life in Birmingham was baseball. The men working the iron mills spent many of their off hours playing the game that was sweeping the nation.

Rick Woodward knew he would inherit the family business, but he recognized that baseball was an important component in boosting the morale of the men who would work for him. He loved the game, played college ball, and believed it could be a good investment for the community and the family business. In 1909, Woodward bought the Birmingham Barons, and in 1910, work on Rickwood Stadium commenced.

Looking Back to Move Forward

The list of Hall-of-Famers who played at Rickwood is a seemingly endless parade of the greatest of all time: Ty Cobb, Dizzy Dean, Joe DiMaggio, Christy Mathewson, Lou Gehrig, Josh Gibson, Mickey Mantle, Reggie Jackson, Monte Irvin, Willie Mays, Satchel Paige, Larry Doby, and Jackie Robinson, to name a few. There is no shortage of anecdotes featuring these players, including reports of a 700-foot blast off the bat of Babe Ruth.

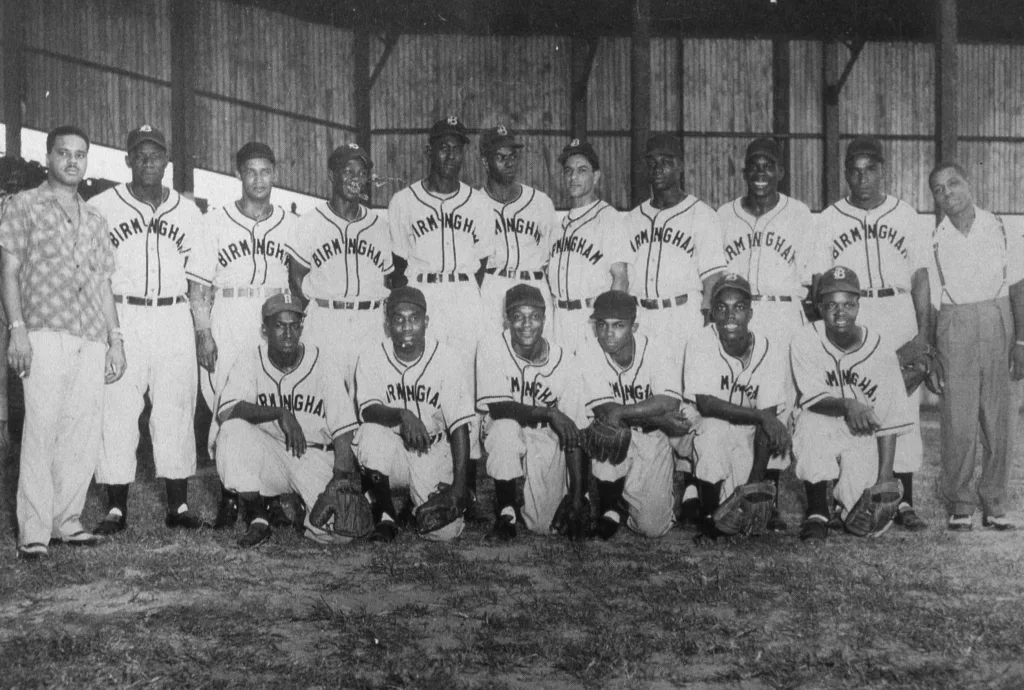

But this summer, the focus is on the Negro Leagues, and the players who made Negro League contests so compelling. The six players featured in the Topps set are preeminent, but the list of standouts is deep, and names like Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, Mule Suttles, and Turkey Stearnes are finally gaining some well-earned recognition nationally.

(Photo by Mark Rucker/Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images)

Birmingham did not avoid the oddities and oppression of the Jim Crow era, but if there was one thing that brought the local citizens together in the early twentieth century, it was baseball. Whenever the Birmingham Barons were out of town, Rick Woodward rented the field to the Black Barons.

According to author Allen Barra, a 1919 Labor Day Negro League doubleheader at Rickwood Field drew 15,000 fans, including some white fans, who sat in the right field bleachers, which were typically referred to as the “Negro bleachers” when the white Barons were playing. These are the strange ironies woven into the fabric of American history.

Like America, Rickwood Field has remade itself multiple times. America’s history of racialized thinking, segregation, and strife is not resolved. If there are ways of healing from trauma that are not the same as forgetting, this summer’s events at Rickwood Field show us the path forward. If (in James Earl Jones voice) “baseball has marked the time,” Rickwood Field can be said to mark one of the key places.