How GPK Took Over Pop Culture

To truly understand the rise of Garbage Pail Kids, one must first understand the media landscape 40 years ago.

“There were only three channels!” is a lie. Cable was around. HBO was around! Even WrestleMania, debuting in 1985, could be purchased on PPV. But the choices were so limited — and recording a show meant buying a VCR — that people generally watched a lot of the same things at the same time.

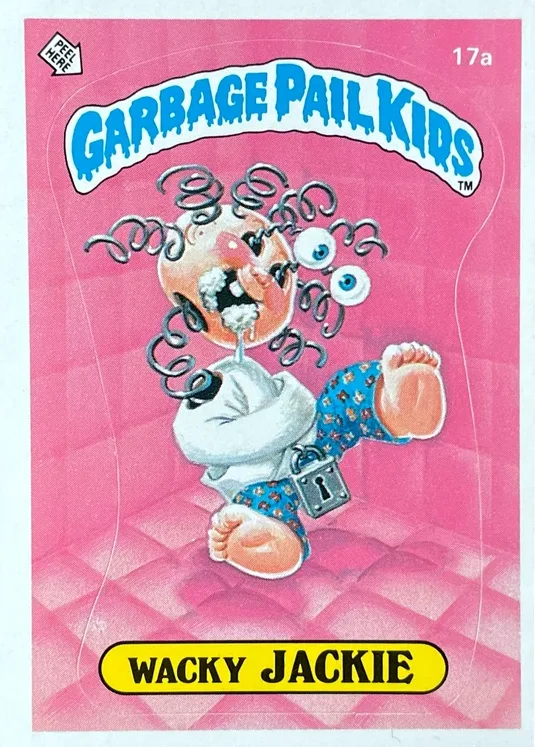

There was no Internet (at least not in homes), so even minor queries had to be researched — or you called someone really smart or with an encyclopedia to ask. And while there were plenty of newspapers, they ran a lot of syndicated columns, so one writer could appear in hundreds of papers across North America at once. In other words, it wasn’t hard to start a media frenzy if something got picked up by the TV news. And if it hit the general consciousness a few days before a holiday, when people got together and caught up? Things could get Berserk Kirk very quickly.

So 1985 was, in many ways, the perfect storm for a Bob Greene syndicated column to catch fire. It ran the day before Thanksgiving, telling the tale of a quiet 12-year-old 7th-grader who discovered a “Most Unpopular Student” Garbage Pail Kid “award” on his desk one day at school. Greene introduced his readers to a stunned teacher and “angry” principal (both nameless and with no indication of the school, location, or any other details), who “couldn’t believe that Topps would sell this kind of thing.” The principal went to investigate at a vague “store across from the school” and discovered more Garbage Pail Kids, sold with a piece of bubble gum, “just like old baseball cards.”

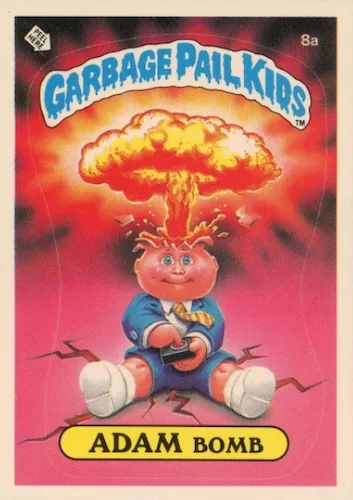

Greene’s story continues in a predictably cornball manner, but, being an early anti-GPK story, it’s missing a key element — rage about the front of the cards. Many early stories focused on those terribly hurtful awards on the back, and not the illustrations on the front.

In early December, Philadelphia Daily News columnist Carol Towarnicky jumped on the bandwagon, bemoaning elements like the Ugly Award, while only briefly focusing on the Kids. “Even the bubblegum that’s included,” she wrote, “won’t settle your stomach when you see the images being sold to grade school children.” She then went on to praise the imperfect He-Man — which also depicts skeletons, she reasoned — for at least having “a moral” to its story.

Adding more fuel to the flames? It was Christmas time, and GPKs were a hot item.

From the Pacifica Tribune on December 12, 1985:

And in the Daily Republican-Register on December 23:

Things were about to get fun. And not just for schoolkids and collectors.

Bad Publicity, Norman Liss, and the GPK Phenomenon

Christmas came and went without any noticeable opinion column attacks, but when the papers started up their rabble-rousing again in January, “Topps Spokesman Norman Liss” became the main character we all needed.

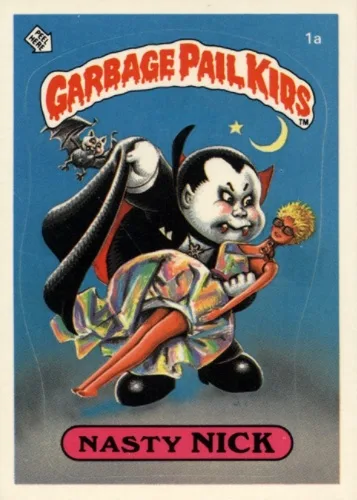

Liss’ job, essentially, was to laugh off any controversy and assure parents and fist-shaking columnists that this was just a limited run series and people were making a big deal out of nothing. Topps, he pointed out, had done this sort of stuff before — Garbage Candy in 1975, Rat Fink Cards, Ugly Stickers, and more. They came and went without much hullabaloo.

But a funny thing happened on the way to limiting GPKs to just one series — demand was through the roof, and frothy media people thinking they were taking ethical stands (not unlike He-Man) were actually just helping to boost the popularity of the cards. Liss even referred to the Greene column as helpful in driving sales.

On January 18, 1986, South Dakota’s Argus-Leader quoted a local distributor who estimated his 28,000 packs of GPK would sell out in a week. In a January 27 story in Louisville’s Courier-Journal, it was reported that the Convenient Food Mart chain had decided to pull the cards off their shelves. Liss noted that the action would mean little to overall sales, as “most stores can’t get enough of them.” The paper talked to a franchisee of Convenient Food Marts who defiantly said he wouldn’t pull the cards from his store because they sold so well. And Terry Smith, a local Louisville distributor, noted that Garbage Pail Kids were outselling Snickers — the No. 1 candy bar in America — 13 to 1.

“There’s no way we’re going to get out of that business,” Smith said.

At the end of the month, a school in White Plains, NY had banned GPK cards. In February, Liss was talking about a third series on the way (this was obviously no longer a limited one-series run) and noted that the cards “cannot be made fast enough” to satisfy demand. Liss also had a classic quote in “Education Week,” noting that “kids are very much into garbage.”

The New York Times eventually entered the fray, reporting on three more schools that banned the cards. But the paper also found a group of parents who didn’t mind GPK, as the cards might encourage children to read, “even if the subject matter is Leaky Lindsey.”

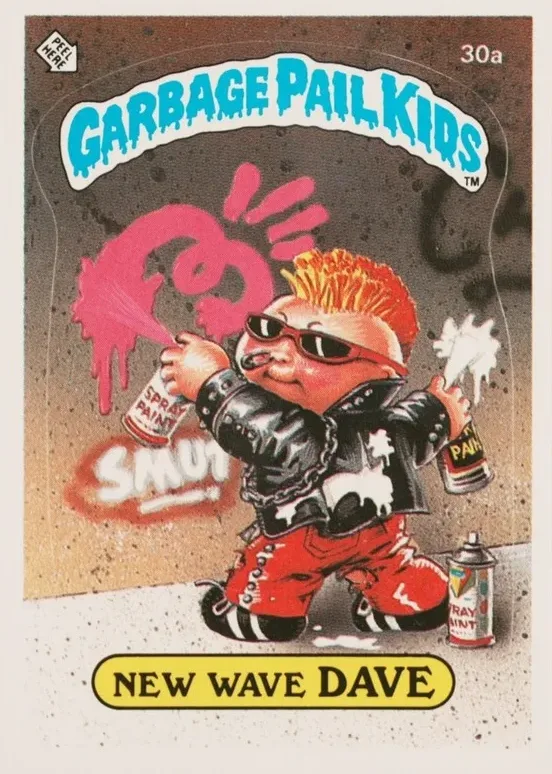

In May, the LA Times reported on another school ban — not because the cards were gross or in bad taste, but because the constant demand and trading created, according to the principal, “a little black market so we had to squelch it.” The story also mentioned a store owner who was price gouging packs up to 45 cents (they retailed for 25 cents) and noted that cards could be found in liquor stores.

By the time July rolled around, people were still expressing disgust at the cards, which had been out for over a year at that point. Some went a little over the top.

“Topps is deliberately trying to subvert the tranquility of our children,” A. James Manchin, then the Treasurer of West Virginia said. “I believe Topps is that little portion of hell that never caught fire.”

By this point, however, it was fruitless. The more Manchin-types brought what they thought was negative attention to the cards, the more popular they became. Liss noted that Topps, now on a fourth series, had “three shifts working” and even brought in extra equipment, and they still couldn’t keep up with demand. The head cashier at an Orlando Kay-Bee told the Orlando Sentinel that “the phone rings all day with people wanting to know if we’ve got them.”

Garbage Pail Kids had won. As Series 6 cards were being run off three printing machines overnight, parents everywhere had to learn the difference between wax packs and rack packs.

The Garbage Pail Kids Legacy Endures

On August 7, 1987, the Masters of the Universe movie, featuring He-Man and, of course, a story involving a skeleton but with a moral, was released. Two weeks later, on August 21, The Garbage Pail Kids Movie premiered. In what must have been a very confusing time period for Carol Towarnicky, the movies ended up playing side by side in theaters across the country:

As for Bob Greene? By the time February 1986 rolled around, he had moved on to offering poorly aged opinions on the Challenger explosion, including an exercise pitting the shuttle tragedy against the Kennedy Assassination and stating that, “within two years, very few people will remember the date of the Challenger explosion.”

And the Garbage Pail Kids? After 40 years, they’re still releasing sets, books, and pop culture ephemera.